May 20, 2020

8 min read

The cancelation of NAB 2020 due to the Covid19 pandemic sent shockwaves throughout the broadcast industry. Held in Las Vegas, NV annually, NAB is the largest broadcast trade show with over 90,000 attendees from over 160 countries. The majority of the 1,600 exhibitors launch new products and technology and for many large companies, up to six months of planning is put into place. Within a very short window of time, the Panasonic Pro Video team had to come up with alternatives in getting its message out while working remotely from home.

In the days leading up to NAB’s cancellation, the team began looking at options for doing a substitute event, including the idea of building a physical booth where customers could visit online. The Panasonic Pro Video team were also in discussions with Paul Lacombe, CEO of New England-based DisruptAR, who specialize in creating virtual productions. Having started his career at General Motors after college, Lacombe has been working in the production industry for 30 years starting at Silicon Graphics in the late ‘80s before venturing off on his own to pursue virtual productions. DisruptAR is focused on bringing AR and VR production costs down for the broader marketplace.

On March 16th, New Jersey, where Panasonic’s US headquarters is based, officially went into lockdown and on March 18th, Lacombe scheduled the first demo for the Panasonic team. NAB 2020 was officially canceled on March 20th. “We had to decide between the two options very quickly,” reveals Panasonic Engineering Manager Harry Patel. “The first option required physically building a booth, bringing in the product while following social distancing requirements (less than 10 people at a time) and bringing in a film crew. It was not practical and we wanted to do something with higher quality, even though we couldn't leave our homes. So, finally, this idea of a virtual event was discussed further and was approved by the end of March.”

DisruptAR's Paul Lacombe doing a virtual demo from his home using the Free-D protocol.

The Challenges of Remote Production

Remote production is not a new concept. Director Francis Ford Coppola famously directed and edited many scenes from his 1982 film, One From the Heart, from a trailer near the set. But creating a production remotely from home during a global pandemic is another story. It was only possible by using state-of-the-art camera technology, VR gaming engines, and cloud-based apps.

For Panasonic, the first goal was to create a clear message with verbal and written communication translated to a more visual video format. At NAB, salespeople would typically communicate with customers on the show floor discussing solutions to each person's problems. Marketing Group Manager Jim Wickizer and P.R. agency, Racepoint Global, were able to come up with a consistent message and worked with individual product managers to present the right talking points.

Patel and Wickizer also began working with Lacombe remotely from his home studio to create video interviews between product managers and a studio host, Zoe Laiz, who were to discuss new products and technology. “We've all had challenging production environments, but to do this remotely with this schedule, it was definitely a leap of faith,” explains Lacombe. “In my gut, I knew this could work but never having done it before was a concern.”

Lacombe converted his 20' x 24' garage into a studio space.

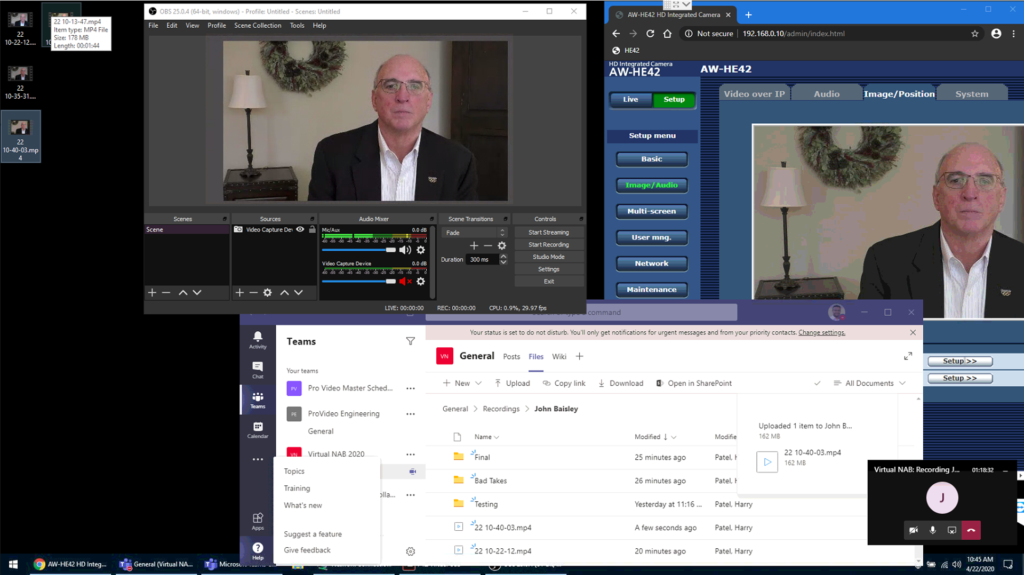

For remote recording, each product managers received a laptop, a Blue Yeti USB microphone, and a Panasonic AW-HE42 Full-HD Professional PTZ Camera. The HE42 was connected via Ethernet and the PTZ Virtual USB Driver and the video was brought into the laptop using OBS to record and TeamViewer for remote control.

Working In Teams

For communication, sharing of files, viewing demos, and monitoring remote production shoots, Panasonic employed Microsoft Teams, a communication and collaboration platform. Overnight, platforms such as Teams, Zoom, Ring Central and many others have allowed people and businesses to communicate with the outside world safely from their homes.

To view what Lacombe was capturing on set during the production, Patel used Teams Screen share creating a quad split using an AV-UHS500 switcher output to a converter box from SDI to USB. The USB feed was presented in Windows as a camera feed, which they shared via Teams.

While supervising the recording of Senior Vice President, Professional Imaging & Visual Systems John Baisley’s opening remarks, through Teams, Patel and Wickizer were able to view Baisley’s living room live and provide direction whether it was a line reading error, a background change or a technical sound problem. Through Teams, Patel was also able to provide screen direction by observing both green screen and virtual set views. “If Zoey was standing right behind a door and enters, we could really see whether or not the shot was good,” explains Patel. “I would tell Paul through Teams, ‘It might work better if she moves over just a tad bit right.’ In terms of remote collaboration, I don't think it would have been possible without the use of Teams.”

While Senior Vice President, Professional Imaging & Visual Systems John Baisley was recording his opening remarks, the team was able to view Baisley’s living room live and provide direction via Microsoft Teams.

“It was pretty cool doing this remotely,” adds Wickizer. “We had a person in Boston, Harry and I were at our homes in New Jersey and we had another person on the West Coast. My daughter came down to our basement once and asked what I was doing. ‘We’re doing a remote production,’ I told her. She really couldn’t believe it.”

Free-D and the Unreal Engine

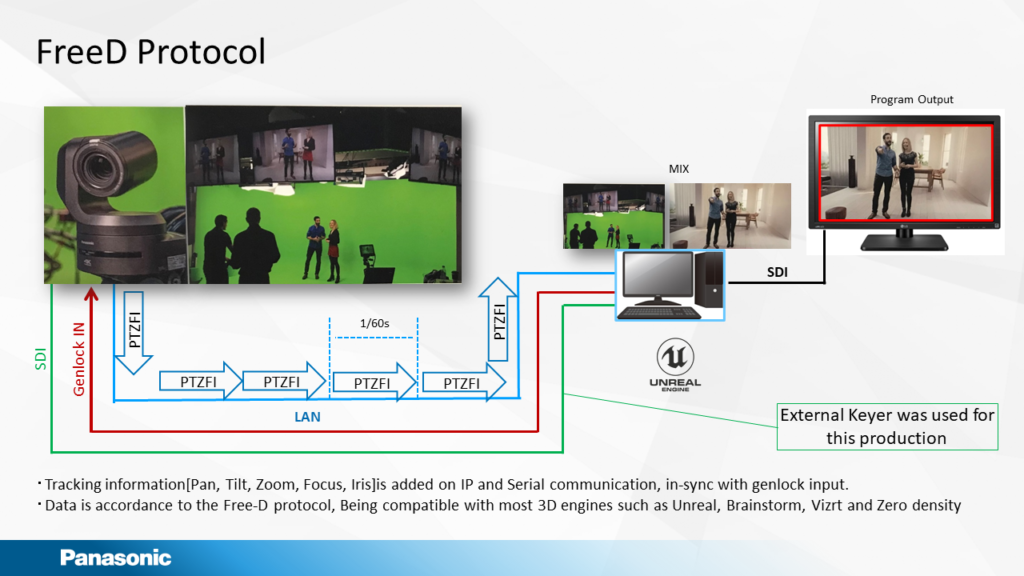

To incorporate realistic VR studio sets into a live production, capturing accurate camera positioning data is essential. Before presenting his first demo for Panasonic, DisruptAR developed a Free-D driver that would allow the AW-UE150 4K Pro PTZ camera to be plugged directly into the Unreal Engine, which provided him the ability to output Pan/Tilt/Zoom/Iris information via IP (UDP) directly from the camera to Unreal’s tracking system live without the need for additional sensors or encoders.

“Free-D came from the BBC back in the early ‘90s as a tracking protocol for one of their camera tracking systems,” explains Lacombe. “It defines the six degrees of freedom – pan, tilt, roll, X,Y,Z, as well as field of view, zoom and focus. Those values are sent down to the virtual rendering engine and connected to a virtual camera so your background responds accordingly in real time at 60 frames-per-second.”

According to Lacombe the Unreal Engine has been used across the board on numerous productions – from The Lion King to The Mandalorian. “It is the underlying technology used by most of Hollywood right now,” says Lacombe. “They’re using it as a proxy for the most part but the goal is ‘final pixel’, which is whatever you’re seeing onset in real time is what is up on the screen.”

The Free-D protocol defines the six degrees of freedom – pan, tilt, roll XYZ, as well as field of view, zoom and focus.

“The Unreal Engine is a gaming engine that has been applied in other markets, including architecture, CAD visualization and in this case, broadcast and film,” says Lacombe. “We’re using it to get to the highest level of photorealism, taking assets from traditional DCC tools like Maya, 3D Studio Max, Blender, using NVIDIA graphics cards at 60 frames-per-second, giving viewers the fidelity of lens characteristics like blooming, flares and de-focusing. The quality you need to get to photorealism and rendering at 60 frames-per-second is essentially what the Unreal Engine does.”

Creating A Virtual World…In A Garage

Lacombe’s studio is in his converted garage that measures only 20 x 24 and his crew consisted of only one assistant. For the green screen, he used a Pro Cyc Portable background. Because of the space limitations, Laiz could walk only a few steps so they were limited on cameras, making the AW-UE150 the perfect tool for the job. In lighting his green screen, Lacombe used 14” LED panels. “The idea is you really want to have one shade of green and get rid of all of the spottiness so your keyer can keep those shadows,” explains Lacombe. “You pick one green that you want to key out and the darker greens are the shadows overlaid in your virtual set.”

Even though he was working in the small confines of his garage, he had to light his talent with the motivated light of a large studio. To light Laiz, Lacombe used two LED panels for both his key and fill. He also used a few spotlights from above to simulate a reddish light coming from the windows. “Basically we're trying to match that direction and that color temperature while not affecting the green screen,” reveals Lacombe. “That's a challenge because you're trying to light the talent separate from the green screen. The barn doors on those LEDs were giving us more room but we were fighting to get away from the green and get minimal bounce off the green onto her clothing and skin.”

On set, Lacombe utilized two UE150 cameras - camera 1 was on the left side and camera 2 on the right.

On set, Lacombe utilized two UE150 cameras - camera 1 was on the left side and camera 2 on the right. When Zoe would do her turn to face a product manager viewed on a vertical monitor, he would switch to camera two at Laiz’s eye level to get simulated product manager point-of-view. Matching eyelines is a challenge but Lacombe says could cheat it a little by knowing where his set home position was. “If you had two cameras, one was 90 degrees to the other at eight feet away and the other one is four feet away, you can measure with a tape measure and put them in the virtual world in that same position. They will adhere to each other through the laws of physics so that they look like they are in that exact position. And then you can cheat a little bit within those guidelines.”

Production Design At The Click Of A Button

For the design of the virtual set, Lacombe used a modified design that he was working with another client the past year. The design was done in Maya and exported into Unreal. Since the virtual set takes place at night, they had a darker look at first but then they decided to make it a touch brighter. He added the Panasonic logo and took away elements that weren’t essential for the Panasonic set. He also added a monitor that comes out of the floor which Laiz walks out from behind it.

In creating your own virtual set, according to Lacombe, there are more 3D assets that are available since online architectural visualization has really taken off. You can go to a 3D library and find 3D assets or models and build it depending on what your customization requirements are. “It’s really a back and forth with the client,” explains Lacombe. “You add your marketing components, branding, all of the colors and materials. Once you have the asset in there, you can take down walls with a button, click or move things around, adjust monitors all in real time. In the 'physical world', this would take a considerable amount of time and money. Once you have the thing built, it's easy to adjust and come back to.”

Host Zoe Laiz interviewing Sr. Product Manager Steve Cooperman about news and content creation.

Keeping A Safe Distance

Virtual production has evolved over the decades through experience and refinement. Although the roles of a physical production and a virtual production are essentially the same, the biggest difference is that everybody is working in the same physical space. Once the stay-at-home ordinance is lifted, whether or not true remote production will become the norm is still being determined.

“There's a reason why you have someone looking at the key, someone looking at the script, someone looking at the camera angles and wardrobe,” says Lacombe. All of those roles still need to be fulfilled and we’re just trying to figure out the best way to do that remotely. So far, it’s worked out amazingly well and we're all surprised by how this came together so quickly and evolved in a natural way. Although we had to wear more hats more than we would have liked for this production, the next logical step is to distribute this even further to have others involved to refine and improve the process. But for the first time out of the gate, I’m very happy with the results and anxious to take it to the next step.”

To watch Panasonic’s virtual event, The Future of Video Production, click through here.

For more information on DisruptAR, visit www.disruptar.com.

![]()